By Martina Mršnik and Dr. Christoph Engler

Limitations and concerns

This is a follow-up on our previous blog entry on large language models (LLMs) and first experiences using the publicly available chatbots, based on LLMs. It is worth noting that during creation of this blog post, the AI technology already advanced and an upgraded version of model GPT- 3.5 (on which ChatGPT was based) has become available (GPT-4).

Large language models

The involvement of technological giants such as Microsoft and Google in the development of large language models (LLMs) for general public makes this technology likely to be soon omnipresent, since any activity on a computer highly depends on their products.

Despite the current global craze, LLMs are not a new technology. Its concepts were developed more than half a century ago. LLMs are, as described by ChatGPT itself, when prompted to provide a definition, “a type of artificial intelligence that have been designed to process and generate human-like text. These models are trained on vast amounts of data, such as books, articles, and websites, and use this information to learn about language and how it is used. As a result, large language models are able to generate coherent text that is difficult to distinguish from text written by a human”.

ChatGPT is based on an LLM called GPT-3.5 (GPT – Generative Pre-training Transformer), a neural network machine-learning model that uses the same pre-training datasets as its precursor GPT-3, which was released in 2020, with additional fine-tuning. This fine-tuning stage includes the incorporation of a concept called “reinforcement learning with human feedback“ (RLHF). ChatGPT is based on GPT-3.5, but works within even stricter guardrails on ethical standards, by introducing human values via strict ethical policies and rules to the model. It is assumed the list of these rules and policies was probably similar to the one published by DeepMind’s Sparrow, which was designed by DeepMind researchers, California Institute of Technology, University of Toronto, and University College Dublin (1, 2). Finally, ChatGPT was GPT optimized for dialogue (3).

GPT-4 is a large multimodal model, which accepts not only text, but also image inputs and delivers text outputs. It is more capable than its predecessor GPR-3.5 in terms of reliability, creativity and handling specific instructions. However, the limitations reported by OpenAI, seem to be similar to those of GPT-3.5, therefore, human review is still needed. (4)

In the previous blog post of this series, we have reported already on the first experiences with ChatGPT for medical writing tasks. In this blog post we focus on the significant limitations and pitfalls that need to be taken into account when using LLMs.

Limitations and caveats

Despite some very impressive skills and interesting results that are delivered quickly, there has been a general consensus among the users, especially within the research and medical community, that current LLMs cannot be considered as a reliable and trustworthy tool yet. The users have been reporting how some results are plain false, are purely made up by the AI tool, and provided references are incomplete. Deceptively, texts are so coherently and confidently written that they can be easily mistaken as a text created by a competent human being (5). We need to remind ourselves, however, that the output has been created by a non-thinking tool. It does not grasp the meaning of the results, and, more importantly, it cannot verify if the provided information is correct. “Contents are a reflection of a collective internet; its creations are generic averages” as put in one of the opinion pieces (6, 7). We also have to keep in mind that the models we explored were developed for a more general purpose and therefore not fine-tuned for medical writing.

Several factors of utmost importance need to be taken into consideration before this technology can be reliably used in everyday practice:

Accuracy

It is known that the LLMs are trained on a big amount of data. In case of ChatGPT the knowledge it received consisted of open source databases until 2021. One can ask the model to take also a specific reference in consideration and this way prompt it into writing more reliable results. The models can be trained by using only a specific set of data sources and references, excluding unwanted or unethical content, as defined by the trainer (i.e., the company that owns the model). Thereby, LLMs can offer more reliable results, whereas, on the other hand, they could be manipulated into a specific direction (knowingly and unknowingly), and therefore provide biased, outright false, even dangerous results. There have also been concerning reports on the ethical implications on the human input needed in the selection of appropriate results (8).

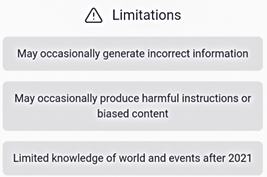

At this moment, accuracy of the results is questionable. Very prominently, upon the announcement of Google Bard’s release a blatant mistake was spotted in the given text (and the company suffered immediate damage on the stock market). Without a laborious factual check, the texts cannot by any means be directly used (9). Also, for some LLMs the data sources are not verifiable, meaning they may contain incorrect information. The incorrect information is therefore being disguised as a correct information, and may be disseminated to the audience by an unsuspecting user. OpenAI itself acknowledges this problem as a limitation on the first page of ChatGPT:

The Limitations that show up on the first page of ChatGPT. Screen shot, source: https://chat.openai.com

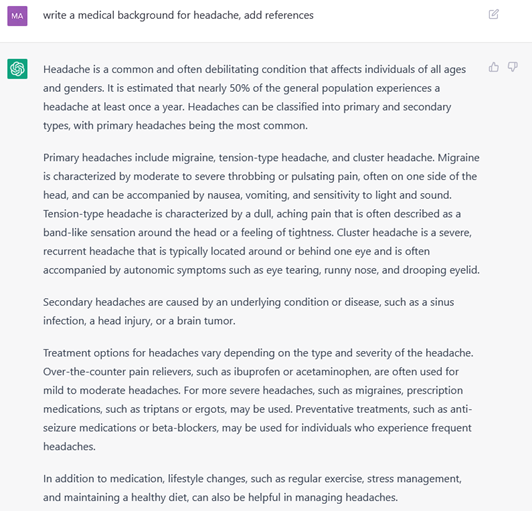

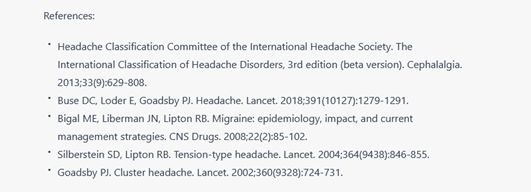

Example of a medical background section as provided by ChatGPT

An example of a medical background section on headache as written by ChatGPT. Legend: ![]() input from GKM medical writer,

input from GKM medical writer, ![]() ChatGPT output. Screen shots have been merged for better readability. Source: https://chat.openai.com

ChatGPT output. Screen shots have been merged for better readability. Source: https://chat.openai.com

Intellectual property

LLMs make use of freely available internet content without disclosing its sources. Moreover, it cannot be verified if the provided texts have been copied word for word as found on other websites, without being labelled as a quote. Further, there is no consensus yet, if the intellectual ownership of a text produced by LLMs belongs to the LLMs’ company or to the individual who gave the prompts to the LLMs.

Data protection (GDPR in EU)

At the moment, the openly-available models (ChatGPT and YouChat) have been created by private companies, which are based in the USA. ChatGPT collects the user’s email address and other personal data and saves the users’ chat history. YouChat is more open and can be used by anybody, there is no need to provide any personal information. At any rate, the terms of conditions must be scrutinized to ensure that companies do not use and sell personal data.

If not addressed and regulated in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR, 95/46/EG), this may lead to restrictions for users in the European Union. The upcoming LLMs will have to take this into consideration if they want to stay in business in Europe.

Confidentiality

In the field of clinical research and pharmaceuticals, where new drugs are being tested, confidentiality is given the highest priority. In case someone is trying to create a text with information on a specific new treatment and study indication, confidentiality must be ensured. Open programs that can be used by anybody, potentially collecting and distributing confidential data, do not fit into this equation. In the future, general-purpose LLMs should adequately protect entered data and offer confidentiality. Alternatively, there could be specific offerings by paving companies using higher degrees of protection for confidential data, which could be also fine-tuned (specialized) for a certain field and available only to their clients. Until then, users should not use any confidential information as a prompt.

The future of medical writing

In the medical field and in clinical research specifically, professionals require precision and accuracy since the stakes can be very high. The programs and tools that are used in the process of product delivery need to be therefore highly reliable. At the moment, the current openly available LLMs, which we tested, do not yet offer this quality. User still needs to put a lot of effort into reviewing, correcting and amending the results, and recognizing the facts from false information. Taken together, the workload is not reduced.

The ChatGPT output may be used as a guidance tool and provide a general idea of a document text. However, the product still lacks the fine-tuning. It remains to be seen, if an updated LLM version may ever surpass the quality of the document created by experienced medical writers who have been perfecting and working with elaborate templates, which take also into account the latest regulatory requirements.

The current LLMs have however proved themselves as a promising tool that may be regularly used in the future and can assist with creation of the final content, given that ALL of the above mentioned concerns will be seriously addressed by the manufacturers.

The input and a review of a professional are unavoidable and the need for that will remain in the future.

The technology is advancing quickly and new, improved versions of LLMs, which can also recognize images, are already available (4). We need to adapt accordingly, by playing an active part in the development and follow its advancement with a critical eye, always requesting that the users’ concerns are addressed satisfactorily.

AI advancements may seem for some people a nuisance, or just like reading a science-fiction novel, but “resistance is futile”, in the words of “Star Trek’s Borg” (10). We can, however, confidently suspect, that additional human input will always play an essential role in dealing with such AI tools. After all, before accessing the ChatGPT interface the user still has to click on the pop-up statement “I am not a robot.”

Literature Cited:

- DeepMind Sparrow Dialogue model: Prompt & rules – Dr Alan D. Thompson – Life Architect; 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: URL: https://lifearchitect.ai/sparrow/.

- Dr Alan D. Thompson – Life Architect. GPT-3.5 + ChatGPT: An illustrated overview; 2023 [cited 2023 Jan 24]. Available from: URL: https://lifearchitect.ai/chatgpt/.

- OpenAI. ChatGPT: Optimizing Language Models for Dialogue. OpenAI 2022 Nov 30 [cited 2023 Jan 9]. Available from: URL: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/.

- GPT-4; 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 15]. Available from: URL: https://openai.com/research/gpt-4.

- Else H. Abstracts written by ChatGPT fool scientists. Nature 2023. Available from: URL: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-00056-7.

- Bogost I. ChatGPT Is Dumber Than You Think. The Atlantic 2022 Dec 7 [cited 2023 Jan 17]. Available from: URL: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2022/12/chatgpt-openai-artificial-intelligence-writing-ethics/672386/.

- Kang JC. Could an A.I. Chatbot Rewrite My Novel? The New Yorker 2022 Dec 9 [cited 2023 Jan 17]. Available from: URL: https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/could-an-ai-chatbot-rewrite-my-novel.

- Perrigo B. Exclusive: OpenAI Used Kenyan Workers on Less Than $2 Per Hour to Make ChatGPT Less Toxic. Time 2023 Jan 18 [cited 2023 Jan 25]. Available from: URL: https://time.com/6247678/openai-chatgpt-kenya-workers/.

- Daily IB. Google Stock Keeps Falling After Bard Ad Shows Inaccurate Answer, AI Race Heats Up. Investor’s Business Daily 2023 Feb 9 [cited 2023 Feb 10].

- Borg; 2023 [cited 2023 Mar 16]. Available from: URL: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Borg&oldid=1143458764.

Picture: @Angelov/AdobeStock.com